Does Britain Still Value Life?

As MPs vote on legalising euthanasia it becomes clear our authorities have failed to protect British children from rape gangs

Towering Columns

In the Daily Mail, Shadow Justice Secretary Robert Jenrick explains how doctors were wrong about how long his grandmother had to live - and why he is voting against assisted suicide.

The doctors told my Nana that she had just a short while left. They were wrong, like they are in many cases. She lived for almost a decade until her death at the grand old age of 94. With assisted dying legalised, inevitable mistakes like this would be too terrible to contemplate.

But for me, it’s the examples around the world where assisted dying is legal that prove it’s a bad idea. In Oregon, under 30 per cent of the patients dying by assisted dying do so because they’re in physical pain. The overwhelming majority die because they fear ‘losing autonomy’ or feel a ‘burden on family, friends and caregivers.’ These numbers are the same just about everywhere data is collected.

That fills me with dread. My Nana felt like she was a burden. I know how much she hated the indignity she felt at having to ask my Mum or us to help her with basic needs. People like her, and there are many such people, may consider an assisted death as another act of kindness to us. How wrong they would be. It’s easy to make laws that work for 80 per cent of people. It’s very hard to make them work for everyone. It’s Parliament’s role to represent that minority, but the Assisted Dying Bill leaves them exposed.

For The Telegraph, Nick Timothy says a national inquiry into Pakistani rape gangs must be honest and transparent with the public.

So we will need clear answers to important questions about the inquiry. Following the death of Dr David Kelly, one of Tony Blair’s senior advisers reassured colleagues about the subsequent inquiry, saying, “don’t worry, we appointed the right judge”. The identity of the person who chairs this inquiry will be vital, and it may need to be a judge from another Commonwealth jurisdiction, to avoid conflicts of interest or social or political beliefs that prejudice the work.

The inquiry will need to be unsparing about the most sensitive subjects: about ethnicity, religious identity, family structures and social attitudes among members of the Muslim population in Britain. What role did clan identities play? Why did social workers make choices that made them complicit in abuse, instead of confronting it? How many police officers were corrupt or complicit? What role did local councillors play in keeping the scandals a secret? What about other public services, like schools, GP surgeries and hospitals?

One of the reasons our politics is so crisis-ridden is the gulf in values and expectations between the governed and the government. The campaign to delegitimise public opinion – about the rape gangs and many other things – shows just how authoritarian our liberal leaders are. The reason they are afraid of the public is that they know they will, soon, be smashed. But it is time now for the truth, and time, too, for justice.

For The Times, Juliet Samuel argues that both Left and Right have been overly dogmatic about “openness”, assuming other nations and cultures will ultimately behave as we do.

[I]mmigration from developing countries occurred in such numbers that it was entirely possible for a man from a remote, religious community halfway around the world to transplant himself into a minicab-driving version of exactly the same culture, populated by men from the same extended family, only now with ready access to an entirely unprotected community of outsiders in the form of girls in care homes or broken families. And the fact that, as far as we know, such men are not over-represented in other kinds of sexual crimes, but have tended tended towards group-based exploitation of vulnerable “foreign” girls, suggests that this is exactly what was — and is still — going on.

More fundamentally, even though we must of course allow for the existence of perfectly decent men who find themselves in societies with sexually depraved norms, we must also understand that culture runs deep. People from very different countries, religions, sects, tribes, rural or urban backgrounds, university or school education levels will by and large have very different norms and beliefs, many incompatible with those Britain has fought to cultivate over centuries. And why should British norms wield any more power over the soul of a man than those of his own family or tribe? It is frankly reckless and demented that our immigration system takes no account of this whatsoever. Openness to all means openness to the bad as well as the good.

But whereas the dogma of openness has more advocates on the left, the right is also afflicted by its own doctrine of “openness”, even in the face of great danger. Broadly, this takes the form of commitment to free trade no matter what, yet again based on a belief in the universal sameness of all societies. It was said, after all, that when China joined the World Trade Organisation, whatever its norms and political institutions, it would become “just like us”. Freedom would follow wealth, and market economics would follow freedom. Instead, China used its economic power to double down on its model, to coerce and buy up our universities, to infiltrate our politics and to dominate critical supply chains.

In The Telegraph, Lord Frost says the Britain he knows and loves is changing rapidly beyond recognition.

Some commentators on social media now go one step further and now, humorously or derisively, call us not the UK but the “Yookay”. As you’ll find if you google them, the term was initially used to symbolise the particular aesthetic quality of much of the modern UK, that jarring mixture of cultures bolted onto the pre-existing British environment. The American candy store next to the kebab shop with its modern signage stuck onto a half-timbered building. The scattered Lime bikes and discarded Deliveroo bags slung wherever on the street. And the soundtrack of modern Britain, multicultural London English with its global slang, the drill music on the train without headphones. If you live in a city, you recognise it.

But the “Yookay” now has a wider implication too: to suggest with the new name that we are now a new country, an actual successor state to the old Great Britain, distinct from it as I have described. And indeed we are becoming it: the Wessex or Mercia to Roman Britain, the “island of strangers” in Starmer’s genius phrase, grottier, “scuzzier” as The Spectator put it the other day, with a different national character, and with lower national ambition. Happily the transformation isn’t complete yet. We don’t have to become the Yookay. We don’t have to live out our days like Roman villa-owners farming our estates as things collapse around us.

Economic, social, and political reform – everything I have been setting out here over the years – can get us back on track. But for that we need politicians who can see what’s going on and who care enough to get the country moving again – and who can reach back to the past, back beyond that break in continuity, to get the national energy to make it happen. For as George Orwell put it, in the final words of his great wartime essay The Lion and the Unicorn, “we must add to our heritage or lose it, we must grow greater or grow less, we must go forward or backward. I believe in England, and I believe that we shall go forward.”

For Engelsberg Ideas, Charlie Laderman assesses historians’ claim that America in the early 20th century was built on the twin objectives of new territory and new markets.

Despite America’s industrial might and the conspicuous wealth of its robber barons during the Gilded Age, fears were growing about the future of its economy. The most famous jeremiad was sounded by Frederick Jackson Turner. In an address to the American Historical Association in 1893, he argued that the ability to expand and occupy new territories was vital to the health of American democracy. Turner suggested that the final settlement of the West and the disappearance of the frontier would have dire consequences for the American way of life. New frontiers and opportunities would need to be found beyond America’s borders. As Turner declared, with the US ‘fully afloat on the sea of worldwide economic interests we shall soon develop political interests’. The Panic of 1893, devastating for the economy, seemed to confirm the urgent appeals of Mahan and Turner. ‘Expand, or explode, is a fundamental law’, as one historian put it, ‘and America, bursting with power, was prepared to follow its dictates.’

For the influential New Left group of historians that dominated American college campuses in the late 20th century, it was the voracious search for overseas markets to offload its surplus products that motivated the US to become an imperial power. Their argument was that this not only propelled the US into war with Spain in 1898, acquiring overseas colonies in the Pacific and Caribbean in its wake. More importantly, it also led to an ‘informal empire’ with the US assuming economic and political control over nations without the need to impose direct colonial rule. Confident in the strength of the American economy, so the argument went, policymakers were convinced that, backed by an aggressive foreign policy, this would ensure the nation’s pre-eminence in global markets.

The argument that these economic interests drove US global strategy is, however, greatly overstated. It is true that a number of politicians, manufacturers and agrarian businessmen urged the capture of foreign markets and warned of the consequences unless buyers were found for America’s surplus goods and produce. But it is hard to see much impact of this rhetoric on government policy. America’s merchant marine continued to languish. Despite expansion into Asia prompted by visions of a vast China market, by 1900 the whole of that continent only accounted for five per cent of US exports. The vast majority still went to Europe. And calls for lower tariffs to stimulate foreign trade were fiercely resisted by the dominant Republican Party, who feared pressure for reciprocal tariff reduction on America’s own rich, domestic market. Above all, alarm at production outstripping American domestic consumption proved exaggerated. Even as US exports expanded five-fold at the turn of the 20th century, they remained about eight per cent of American GNP, vastly less than the 26 per cent it comprised in Britain.

In The Telegraph, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard suggests President Trump may favour strikes against Iran over accepting a US energy price crisis.

Iran does not want a parallel conflict with Sunni Arab states. It is already reeling from the loss of its strategic ally in Syria, and the decapitation of its Hezbollah proxies in Lebanon. It repaired ties with Saudi Arabia two years ago in a deal brokered by China. Nor does it want to irritate China. But there are limits to forbearance if the regime is pushed to the wall. “We do not think the Iranian leadership will prioritise keeping crude supplies steady to China over trying to ensure their own survival,” said RBC’s Ms Croft. Oxford Economics said a full-blown oil crisis of this kind would push oil to $130, and push both global and US inflation to 6pc.

It is China that now depends most on oil and LNG from the Gulf. America imports almost no fossil fuels from the region, except for a little Arabian heavy crude to balance its refineries. That shields the US from immediate supply risk, but not from a price shock. Arbitrage through the futures market instantly links US and global oil prices. Petrol at the pump shoots up for Americans too in such a crisis. They drive twice as far as Britons or Germans on average, and their cars use 50pc more fuel per mile.

Donald Trump may conclude that it is better to join the war and drop his bunker-buster on Fordow rather than risk a cost of living shock on his watch. But that would create a far-reaching and dangerous situation of a different kind. Let us never forget one fact: it was Trump who petulantly tore up the original six-power nuclear deal agreed with Iran in 2015. It was he who undercut the moderate faction in Tehran, provoked the ultra-hardline backlash, and caused the nuclear crisis that now haunts his presidency. Does the game show president even begin to understand what he did?

Wonky Thinking

On his Substack, Ed Conway dives into what causes the price of a can of tinned soup to spike, tracing the volatility of global steel markets and the impact of Trump’s trade war.

All of which is to say: making this kind of steel is quite hard, and, for the time being at least, those who decide metal grades and processes have determined that only blast furnace iron will do.

Oh, and there are only so many companies around the world making it. There’s plants in the Netherlands, in Germany and Korea. There are some makers of DWI quality steel in China, where the quality was historically below par, but is improving all the time. And for decades, packaged steel has been one of the proudest products of the steel mills of South Wales, owned these days by Tata Steel.

Tata recently shut down the blast furnaces at Port Talbot, with an audacious (and controversial) plan. The superficially audacious part you probably already know about: they would replace all their steelmaking with an electric, and much lower carbon, alternative. There are all sorts of reasons this will be hard - not least the fact that Britain has the highest electricity prices in the developed world. But actually that’s not the really daring bit. The really daring bit is that they also want to become the world’s first scale producer of electric arc furnace-made DWI steel.

No-one has managed to make recycled steel at scale that’s consistent and reliable enough that if you stretch it out like a balloon it maintains its integrity. Tata think they have a chance to crack this nut. But the more you understand about the nature of this kind of steelmaking, the more you realise that what’s happening in Port Talbot is even more of a gamble than is widely appreciated.

Anyway, the other important thing to note is that America, most of whose steel is made these days not in blast furnaces but electric arc furnaces, doesn’t make anything like enough DWI steel to satisfy its demand for cans. And since no-one is building new blast furnaces, it’s not likely to any time soon. So, for the foreseeable future it will have to import it in from overseas.

About 80 per cent of American tin cans are made from imported steel. And since that steel can’t easily be substituted, the companies that make those cans will have little choice but to pay the tariffs imposed by Donald Trump.

None of this ought to have come as a surprise to the White House. Last time they imposed tariffs on metals in 2018, they eventually excluded certain products, like these, that couldn’t really be substituted or reasonably quickly replicated domestically. This time: no exceptions. Steel importers face 50 per cent tariffs on everything. So if things continue as they are right now, it’s pretty inevitable those costs will eventually spill into the US economy, potentially being passed onto consumers in the form of more expensive condensed soup (and other tinned items).

But this brings us to the much-hyped trade agreement with the UK. As you’ll no doubt be aware, President Trump has announced a deal with Britain, which will permit it tariff-free access for steel and aluminium, as well as for a certain number of cars and aerospace products. That would be a big deal for American tinned food producers, because right now a significant chunk of their DWI steel comes from… Tata Steel in Port Talbot.

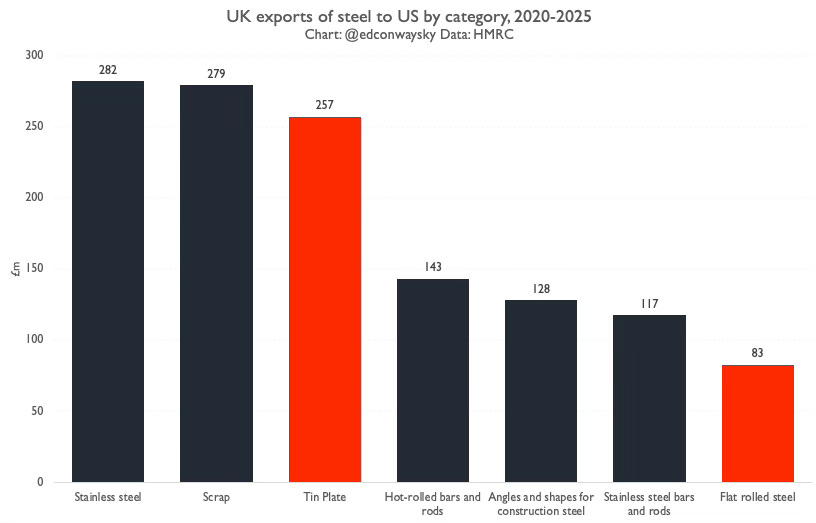

Indeed, look at the UK’s steel exports to the US by category and you can see packaging steel, or “tin plate” as it’s also confusingly known, is the third biggest category. I’ve marked the types of steels that come from Port Talbot in red here. For all that Britain might not make much steel these days, it’s actually quite important when it comes to tin cans.

Sidenote: this is a reflection of the way the global steel market works these days. Rather than trying to make every kind of steel, many countries now tend to specialise in certain varieties of steel, with the presumption that, since it’s a global market, they can just buy in the other stuff from elsewhere. So Britain is a moderately big player in tin cans and coil, but it doesn’t make any weapons-grade steel (that’s Sweden) or plate steel (mostly Asia).

Anyway, back to that trade “deal”. In theory, it could ensure at least some tariff-free DWI steel gets into the US. Welsh mills could help save American tinned food buyers a good few cents! But, despite being proudly announced by Trump and Keir Starmer many weeks ago, only the car and aerospace part of the UK-US agreement has actually been formalised. The metals deal is seemingly missing in action.

Why? It comes back, in part, to those blast furnaces in Port Talbot. Because Tata has shut down the furnaces and has yet to build the electric arc furnace that will (in theory) replace them, it is temporarily having to ship in most of its virgin steel from the Netherlands and India. That steel then gets processed in its existing plants and turned into the DWI its customers have come to expect.

The upshot is that the DWI steel being made in South Wales was actually “melted and poured” (a key bit of terminology in steel) somewhere else altogether. Strictly speaking, it’s not really UK steel at all. It’s just processed here.

That might seem like a moot point, but for the American trade negotiators it’s all-important. They have insisted in talks with their British counterparts that only steel “melted and poured” in Britain should be entitled to be tariff-free. And if that stays the case, even Tata’s DWI steel will face the same tariffs as everyone else.

On the Peter McCormack podcast, Gavin Rice discusses the stagnation of the British economy, why Liz Truss’s diagnosis was wrong and how politicians’ failed the public over mass migration.

Quick Links

The official Casey Report into rape gangs found that councils and police forces systematically covered up the ethnicity of perpetrators.

Parliament voted to decriminalise abortion up to birth.

Sir Keir Starmer told President Trump domestic terror attacks in Europe may follow if the US strikes Iran.

The Government is considering measures to cut industrial energy prices…

…but the UK’s largest fibre glass factory is due to shut down.

Council tax bills are set to rise in the south to help subsidise the north.

One in every 20 homes in the UK is now priced at £1 million or more.

The Bank of England held the base rate of interest at 4.25%.

In 2028-29 the Department for Health and Social Care will account for 49% of Whitehall-controlled spending.

British workers have access to a third less capital than their counterparts in more productive countries.

Poland’s GDP per capita rose from Iran-levels to Japan-levels in a single generation.

I'm surprised that anyone still pays attention to the Tory press. They should hide away in shame