Are the wheels already coming off?

Riots, prisoner releases, strikes, union pay deals and scrapped investment are defining Labour's first hundred days

Towering Columns

In The Telegraph, Robert Jenrick says the Conservatives fundamentally failed to deliver an end to mass migration during their time in government.

While the date of the election was clearly a mistake, we lost because, for 14 years, we failed to deliver our promises on the economy, the NHS, and most consequentially of all, migration. The public aren’t obsessed with this topic. They do not wish to spend every day thinking about it. They just want action to match words. And despite the rhetoric of the Labour Party, Sir Keir Starmer’s policies tell a different story.

Despite the increase in spousal visas, Labour have already scrapped the plan to raise the minimum income requirement for family visas from £29,000 to £38,700. It’s a return to the type of low-skilled immigration that has burdened, not boosted, our economy. They are also considering bringing back free movement with the EU for those under 30. Of course there is a place for highly selective and capped youth mobility schemes, but this proposal is neither. It would be an insult to the 17 million who voted for control over our immigration system.

And as the Budget approaches, expect to see the Chancellor pushing for visa liberalisations as an easy way to inflate GDP figures. The headline growth rates might be higher as a result, but it doesn’t translate into more money in the pockets of working people. In fact, the evidence suggests it will suppress living standards and deter productivity investment. Migrants can bring skills, but they don’t bring homes, GP surgeries or motorways, so our capital stocks are diluted between more people…

…[T]he only way to end the cycle of broken promises is to create a legally binding cap on immigration. That figure should be in the tens of thousands – or less – as was the case before the onset of mass migration initiated by Tony Blair. Our goal should be to become the grammar school of the Western world, attracting top talent – those that contribute more in taxes and skills, than they take out in services. It won’t be plain sailing but we must do it.

In The Critic, Sam Bidwell says relying on immigration for a supply of doctors is unnecessary and increasingly unsafe.

In reality, [the shortage of doctors] is an entirely artificial problem. In consultation with the British Medical Association, the Government caps the number of training places at UK medical schools. Currently, this stands at 9,500 trainees per year, though there are indications that this might be increased over time to 15,000. When the cap was temporarily lifted in 2020/21, demand for medical places shot up — before the cap was reimposed in 2022. This whole absurd system stems back to 2008, when the BMA voted to cap the number of medical places and ban the opening of new medical schools. At the time, they cited a fear of “overproducing” doctors, which risked “devaluing the profession”. Of course, maintaining the cap suits the BMA and its members just fine — fewer doctors trained here in the UK means less competition for highly-paid consultant roles.

Truth really is stranger than fiction. We cap the number of medical training places for medical students, which creates gaps in the healthcare service — rather than training more people, we import foreign-trained doctors to fill those gaps. We’re then told that we “need” migration to keep the system going. Clearly, this isn’t true. The obstacle to a self-sustaining NHS workforce is the UK Government’s unwillingness to make a long-term investment in the UK’s domestic workforce. Between 2010 and 2021, 348,000 UK-based applicants were refused a place on a nursing course. A House of Lords report from late 2016 found that, in 2016 alone, 770 straight-A students were rejected from all medical courses to which they applied. Without the BMA’s absurd protectionist cap, these students would now be entering the NHS workforce.

And it’s not as if we’re trading low-quality domestic trainees for high-quality foreign imports, either. Foreign-trained doctors are 2.5 times more likely to be referred to the GMC as unfit to practice than British-trained doctors — and there’s plenty of variation depending on national origin. Bangladeshi doctors, for example, are a staggering 13 times more likely to be referred to the GMC than their British counterparts.

The Boom substack reveals that one in every 50 Taiwanese babies is now born to parents employed by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) - and considers why.

Taiwan makes 65% of the world’s semiconductors and TSMC, which is Taiwan’s most profitable company, produces most of them. Workers at TSMC know that they are working at the leading company of an industry that accounts for 15% of their nation’s GDP. Their skills are in demand, they are well remunerated, and enjoy many perks that exceed Taiwan’s statutory requirements, such as extra annual leave and paid sick leave.

In response to the TSMC story, demographer Lyman Stone pointed out that chance of parenthood and status are positively correlated for men, globally. At Boom, we’ve touched on this effect when writing about Finland: across the Nordic countries, those most likely to be childless in society are men of a low education level. In having a socially useful, well paid job, TSMC workers are likely receiving a fertility boost, because it is easier for them to set up their own household and to partner.

We also know that individual financial uncertainty depresses birth rates, while individual financial certainty increases them. Because of their in-demand skills and the nature of their work, TSMC workers may be more sure of their position and their earnings than other types of employees in Taiwan, also making them more likely to start a family or have another child. There’s evidence that other tech workers in Taiwan are benefitting from a similar effect…Others have written how Hsinchu, the city which hosts Hsinchu Science Park (including a TSMU campus) and is known as Taiwan’s Silicon Valley, has the highest average household incomes in Taiwan and is enjoying a mini-baby boom, a ‘prosperous family phenomenon’. Hsinchu City and Hsinchu County are the only prefectures of Taiwan where the under 14s outnumber the over 65s. In Guanxin Village in Hsinchu, where 90% of residents work at the Hsinchu Science Park, under 14s account for 29% of the population, as opposed to 11.9% in Taiwan overall.

In The Times, Danny Finkelstein says Labour is pursuing a dangerous and costly new strategy in negotiating with public sector unions.

There is a large literature on successful negotiation, much of which originated with the Harvard Negotiation Project. The central idea is something called the Batna, the best alternative to a negotiated agreement. Before entering into a negotiation, parties are advised to consider what they would do if they were unable to come to an agreement. This establishes your baseline…The last government, essentially, regarded its Batna as accepting that there would be some strike action. This was politically costly — people tend to blame ministers for the disruption, even if they don’t sympathise with the union — and therefore undesirable. So they wanted a deal. But at a certain point they preferred to have strikes than to have to increase taxes or fares to pay to end the strikes.

But now? Well, it is obvious that you will achieve a less good deal if you have a less good Batna — and if you let the other side know what it is. And Labour has now done both. Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, and Louise Haigh, the transport secretary, have indicated that they regard the Batna as being set by the cost of any strike. In other words, the Labour government intends to settle if the financial cost of the dispute is greater than the cost of settling it. A moment of thought reveals the power and incentive this gives the unions. What this principle means is that the more costly the strike, the more money the government will give them.

The new government has not merely adopted this position, but actually informed everyone it has done so. What will the unions do with this information? If they are rational, they will threaten more strikes, and the strikes they threaten will be more potentially disruptive and costly. They will then presumably be avoided, but only at a heavy financial cost. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the doctors’ union is appealing to its members to support a large pay rise explicitly on the basis that it would allow them to come back for more, using the threat of further action. The train drivers are already in a fresh dispute. The unions will press not only for more pay but also for more power and more workplace benefits, for as long as the new Reeves-Haigh principle is maintained. Eventually the government will appreciate that the principle cannot be sustained and it will be abandoned. Unfortunately, we may have spent a lot of money by then. And the unions may have learnt lessons about the weakness of government negotiations that it may take them a long time to unlearn.

Also in The Times, David Goodhart argues that addressing the social and economic grievances of poor whites would help prevent bigotry and disorder.

Decades of economic policy has wiped out well paid industrial jobs and focused growth around financial and professional services; education policy has centred on expanding higher education and ‘saving the clever ones’ who have to leave post-industrial places to achieve; the two parent married family has almost disappeared in poorer parts of Britain along with religious belief and, often, a sense of purpose; direction-providing institutions from trade unions to the armed forces have withered…

…On top of that it is widely perceived in these places that the sympathy of the national political class, and graduate-run local institutions, is directed more towards diversity and minorities, on whose altar national citizen favouritism in jobs and access to public goods is said to have been sacrificed. It’s certainly the case that parts of West and South Yorkshire, Greater Manchester, West and East Midlands, have been changed out of recognition by mass immigration in one generation and starved of the resources and infrastructure to cope with it. Meanwhile, elite Britain in leafy parts of the country has been protected from the consequences of its own ideas.

Plenty of white working-class people have actually progressed well enough in recent years and, according to the Social Mobility Commission, more than two-thirds of what it calls the “lower working class” have been upwardly mobile. Many of the rioters, judging by the stories of previous convictions and chaotic lives, come from what used to be called the underclass. Some are undoubtedly their own worst enemies, having children too young, failing to keep families together, drug and alcohol misuse, no work ethic. Yet poor white people in England are on several counts, including health and education, the most disadvantaged large group in the whole country and their resentment finds a sympathetic echo in a much wider strata of society as opinion polls show. But when protest extends beyond the socio-economic to encompass immigration and their more intangible sense of cultural demotion, official opinion turns cold. No government is going to implement an immigration pause nor embrace an English identity.

There is, however, one thing it could do. And that is to stop using the troubled places where most of the rioting took place as dumping grounds for poor incomers. These places receive more than their fair share of both asylum seekers and housing benefit families from elsewhere needing a roof. It is hard to instil a sense of pride and stability in your town when it has such a large transient population often associated with crime and disorder.

In The New Statesman, Sohrab Ahmari says Trump’s alliance with Elon Musk is not compatible with pro-labour economic populism.

Whatever the relative merits of Musk’s ownership of X, the pseudo-populist right is recapitulating a tired, racialised, and “culturalist” account of labour in defending his actions. A worker, in this telling, is a burly electrician or carpenter who wears flannel shirts and drives a pickup. In reality, the American workforce – people with no means of sustaining and reproducing themselves but for selling their labour power for wages – also includes the likes of university adjuncts, a slew of downwardly mobile professionals, and, yes, tech administrators.

Musk’s anti-worker stance isn’t limited to his employees at X. As I’ve previously detailed, Musk is at war with the entire labour architecture inherited from the New Deal era. Earlier this year, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) filed a complaint against Musk’s SpaceX, charging the firm with unlawful retaliation in firing a group of employees who had dared to criticise the magnate’s online behaviour. In response, SpaceX filed suit against the NLRB in federal court, claiming that the board itself is unconstitutional, since it both enforces labour law and adjudicates disputes. Citing James Madison, the firm claimed this is “the very definition of tyranny”.

Amazon and Trader Joe’s – supposedly “woke” firms routinely denounced by the pseudo-populist right – have joined Musk’s challenge to the NLRB’s constitutionality. They’d prefer to remove all labour disputes to the justice system, with its high costs and cumbersome processes, so that by the time striking workers get their day in court, they will be too exhausted and bankrupt to press on. Already, thanks to decades of rulings from GOP-dominated courts and labour boards, the New Deal order has been hollowed out, with every advantage accruing to bosses. If Musk has his way, that order will be effectively demolished.

This agenda is neither populist nor pro-labour. By cheering Musk’s brutal treatment of his workers, the Trump campaign has sadly vindicated those who saw its pro-worker rhetoric as a mere facade. There is still a chance for Team Trump to prove these critics wrong, for example, by proposing a labour-law reform that levels the lopsided playing field between employers and employees. But time is running out.

Wonky Thinking

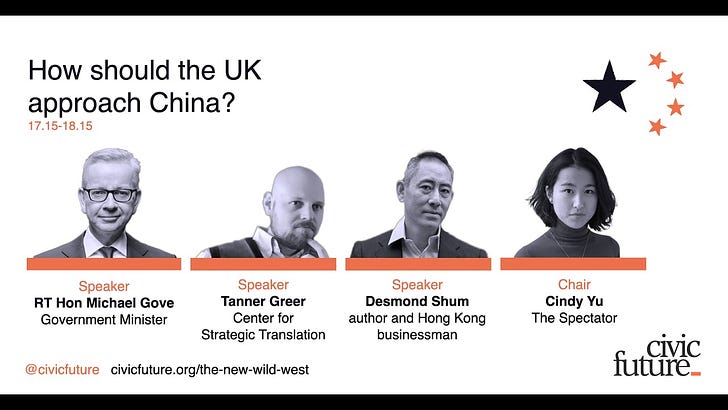

On The Scholar’s Stage, Tanner Greer summarises China’s approach towards geopolitical strategy.

It will be difficult to guide any nation through the storms of the next two decades; it will be harder still if our leaders chart their course without reference to the fundamental ways, means, and ends of Chinese strategy. These ways, means, and ends are discernible. When you clear out the deadwood and the underbrush you will find that the many branches of Chinese foreign policy spring from five trunks, each vital and deep-rooted.

Others might parse the fundamentals of Chinese grand strategy slightly differently. What follows is my personal attempt to summarize the essentials of Chinese foreign policy in as few points as possible. These can be stated as follows:

The overriding goal of the Communist Party of China is to restore China to a position of glory and influence commensurate with its ancestral heritage.

This can only be accomplished by pioneering a technological transformation of the global economy on the scale of the industrial revolution.

The greatest perceived threat to China’s rise is found in the ideological domain—and in a globalized world that domain is a global one.

Chinese leaders imagine they will reshape the global order primarily through economic, not military, tools.

The main exception to this is Taiwan. With Taiwan economic tools have proven ineffective; the possibility of war is very real.

Onward published Venturing Out: The case for a new wave of university partner funds by Anna Dickinson and Allan Nixon, calling for measures to help institutions outside the Golden Triangle build private investment funds to support spin-outs, which are currently disproportionately based in the South East.

Something interesting is happening in Oxford and Cambridge. Since 2015, Oxford University has seen a 166% increase in the number of new companies being formed out of its research each year and a 687% increase in capital raised. Cambridge University has seen a 60% increase in spin-outs formed and a 1,310% increase in capital. In the number of companies surviving at least three years, Oxford has seen an increase of 105% and Cambridge by 178%.

Oxford and Cambridge have historic strengths that are boosting their spin-out potential. But key to their success has been their university partner funds (or partner funds): Oxford Science Enterprises and Cambridge Innovation Capital. Since their establishment, these funds have brought an influx of capital and a wave of talent who help find investable propositions and support them to become successful companies. And through their networks they help attract additional capital from other funds and investors, both home and abroad.

In recent years others have attempted to follow suit. New funds have been set up across the country, including the University of Edinburgh’s Old Street Capital, Newcastle University’s Northstar Ventures, Northern Gritstone and Midlands Mindforge. But there are still too few partner funds serving a narrow set of universities.

Many other universities across the country have the potential to commercialise their research and boost local prosperity but are unable to do so. Why? First, there is a capital deficit outside the Golden Triangle of London, Oxford, and Cambridge. Despite producing 17% of the country’s spinouts, London is home to almost 80% of the UK’s venture capital and private equity firms and more than half of all investment deals. More than two thirds of all deals occurred in either London, the South East or the East of England in 2022.

Second, university Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) are underpowered, lacking the funding, capacity, and expertise to drive spin-outs. British universities are in a deficit of £4.5 billion and have limited scope to invest in innovation. Support through funding pots such as the Higher Education Innovation Fund is insufficient, varies widely between universities and does not reward universities who spin out more companies than others: Southampton University received £5 million in 2022-23 but did not spin out any companies, whereas Imperial received the same and spun out 11. Capacity at Technology Transfer Offices varies significantly. The TTO at King’s College London has a dedicated team of 11, Leeds just two. Queen’s University Belfast’s TTO has less than 10% the staff of Oxford’s.

Book of the Week

We recommend Breaking the Code: Westminster Diaries by Gyles Brandeth. Writing just before the general election, the former MP for Chester and Government whip’s personal journal provides a candid account of his life at the heart of Westminster in the 1990s and a through-the-keyhole insight into life in the Whips’ Office.

Does history repeat itself?

Not exactly. Of course not. But I must say, re-reading my diaries from the 1990s, as I write this in the run-up to the 2024 general election, I can hear distinct (sometimes alarming, sometimes amusing) echoes of the political scene as I found it in the run-up to the general elections of 1992 and 1997. Decades on, much of the past seems to be very present.

The Conservative Party heading for political oblivion: check. (That was the prediction from some in 1992 as well as 1997.) The Conservative Party riven with division: check. (It was all about Europe then, but the deep-rooted fissures remain the same.) The Prime Minister’s a decent guy, competent, conscientious, committed, but is he cutting through? Check. (John Major then; Rishi Sunak now; both, also, regularly undermined by some on their own side.) The Labour leader wresting his party back from the left giving as few hostages to fortune as he can manage: check. (Neil Kinnock, 1992; Tony Blair, 1997; Keir Starmer, 2024). MPs on all sides falling from grace (telling lies, selling favours, dropping trousers), prompting lurid headlines and troublesome by-elections? Check, check, check.

Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose. Indeed, many of the characters you will find in the pages that follow, written thirty or so years ago, are still very much on the scene. David Cameron, for example, first crops up here on Tuesday 9 February 1993, when we both attended the Conservative Party’s Winter Ball. I was there as auctioneer and master of ceremonies. David was there as a special adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. On Thursday 29 February 2024, we were both invited to this year’s Conservative Party winter fundraiser. Once again, I was there as MC, doing the auction. David Cameron was there again, too, as cheery, pink-cheeked and glossy as I had first found him, but now, having been Prime Minister from 2010 to 2016, as Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton and Foreign Secretary.

This is a book about yesterday, but I hope it will resonate today. It is simply an account of my time in politics, back in the day, not as a leading figure (far from it) but as a foot soldier who occasionally found himself inside the general’s tent, a backbench MP who became a government whip, an obsessive diarist fascinated by politics and people.

Quick links

Inflation has risen back to 2.2%.

Nearly 2,000 prisoners are due to be released in a single day in September.

AstraZeneca is threatening to scrap plans to build a vaccine plant in Merseyside as Chancellor Rachel Reeves considers reducing state aid for the project.

The energy price cap is about to rise, adding £12 per month to the average household energy bill.

Family visas are up 35% this month but overall numbers are down.

In the first quarter of 2024, the Government gave more visas to relatives and dependents of Somali nationals than it did to physicists, chemists and biologists.

45% of voters think the Government should resist large union pay rises, versus 35% who disagree.

500 academics including Sir Richard Dawkins wrote to the Education Secretary protesting the scrapping of university free speech laws.

The UK has one of the highest costs of railway building per kilometre.

Levels of concern about immigration are becoming increasingly polarised between Conservative and Labour voters.

Ministers are considering agreeing an EU free movement deal for under-30s.

67% of voters are aware of Labour’s policy of cutting winter fuel payments but only 28% support it.

Youth unemployment has risen in Canada as it has expanded its foreign worker programme, with large influxes into hospitality and retail.